2.2. Shared Value Approach and ECG Model

Porter and Kramer [

32]

(p. 6), defined shared value (SHV) as “… policies and operating

practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while

simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the

communities in which it operates. Shared value creation focuses on

identifying and expanding the connections between societal and economic

progress …”

Hence, the underlying idea is that

firms can simultaneously create economic, social and environmental value

(i.e., customer’s welfare, natural resources over-exploitation, key

suppliers’ sustainability and/or disadvantage situation of local

communities in which the company operates) [

33]. By all what has been pointed before, Porter and Kramer [

34]

pointed to SHV to be a concept that goes beyond Corporate Social

Responsibility (CSR). According to them, CSR conceives social value

creation as somewhat peripheral and, always subordinate to economic

value creation, in the firm’s strategy. In this sense, for them, CSR

policies are the consequence of the firm’s search for social legitimacy,

thus, maximizing short-term profits [

32].

Therefore,

by means of SHV, they redefine capitalism borders as the focus on a

different aspect to lever the businesses’ competitive capacity [

35]:

i.e., reconceiving products and markets, redefining productivity in the

value chain and developing local clusters. According to them,

reconceiving products and markets consists of identifying the new needs

of societies in fields of healthcare, housing, environment, etc.,

generating innovating products to fulfill those needs co-creating value

for the environment, society and businesses. On the other hand, by means

of redefining productivity in the value chain, i.e., reconfiguring the

activities of the value chain from the perspective of the SHV,

businesses enhance the use of resources, logistics, energy and

employees’ productivity, thus minimizing resource waste. In addition,

local clusters development allows the implementations of improvements in

different business areas by means of cooperation with local businesses

(suppliers, customers, competitors) and also with different types of

local institutions (business associations, local bodies, etc.).

However,

a strategy based on SHV is a bet for the long term as their outcomes

can involve longer time period and higher initial investment “… higher

return and broader strategic benefits to all the participants …” [

32] (p. 4).

As

in the case of the ECG model, such approach confers an important role

to market transparency, as well as to cooperation as an essential

condition to create SHV (i.e., cooperation between the firm and its

supply chain) [

36,

37]. However, unlike the ECG model, SHV model does not advocate for replacing competition with cooperation.

Another

key difference between both models is the role they give to business’

profits. In the case of SHV, the underlying idea consists of the

simultaneous co-creation of social (in a broad sense which includes

environmental) and economic value. Therefore, SHV considers social and

economic value creation as goals at the same level. In this sense, the

SHV model provides full legitimacy to business growth as a strategic

goal. Conversely, the ECG model considers business’ profits and economic

value creation merely as a means that allows businesses to contribute

to the common good. That is, as a mean to generate social and

environmental value.

Despite these differences, the underlying logic proposed by Porter and Kramer [

32] about how to create SHV can lever the future development of the ECG model [

38,

39].

Some of the actions that drive to SHV creation are also a way to

integrate the ECG values into business behavior: human dignity,

solidarity, social justice, environmental sustainability, transparency

and co-determination.

However, we must take

into consideration that SHV approach does not include business’ ethical

values; instead, such issues are relegated to a second term [

40].

For that reason, according to the SHV approach, businesses can

co-create social and economic value, but such approach will not

guarantee business’ legitimacy because it does not guarantee that

businesses assume full responsibility for their actions [

41,

42].

2.3. Triple Bottom Line and ECG Model

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) has its origins in Carroll’s pyramid [

43,

44,

45].

Thus, Carroll’s pyramid points to the existence of four types of CSR:

economic responsibilities (be profitable), located at the base, on a

second level, there are the legal responsibilities (obey the law as

society’s classification of what is right or wrong), on a third level,

we find ethical responsibilities (be ethical, obligation to do what is

right, just and fair and avoid harm), finally, on the top of the

pyramid, we find philanthropic responsibilities (be a good corporate

citizen, contribute resources to the community, improve quality of

life). The ECG framework tries to operationalize the concerns related to

ethical and philanthropic responsibilities of the firms, i.e., those

voluntary adopted by the firms [

46,

47].

Following Elkington [

10]

(p.3), “the sustainable development is compromised with economic

prosperity, environmental quality, and social justice”. Thus, it takes

into consideration three different lines: society, economy and

environment. Society depends on the economy and this, in turns, depends

on the global eco-system whose health is represented as the third line

of the TBL. Society should be viewed in terms of its relations with

economy and eco-system, giving birth to a set of relationships among the

three lines [

48,

49].

The

TBL model employs a matrix to measure in a quantitative way the impact

generated by the organization from an economic, social and environmental

point of view [

50].

Such three dimensions are neither static nor stable; on the contrary,

they are viewed from a dynamic perspective due to the consideration of

the organizational environment in the model. Thus, every one of the

lines acts as a continental platform which can move independently from

the others. So that it can be placed above, below or beside the others;

this involves the possible existence of frictions among them [

51,

52].

Notwithstanding

the above mentioned, the matrix relates the three basic dimensions

(economy, society and environment) with the organization’s stakeholders

(shareholders, franchisees and/or subsidiaries, employees, customers,

competitors, local communities, humanity, future generations and the

natural world or eco-system).

The model has

succeeded in the last years as it has served to design and implement CSR

policies. It is possible to explain its growth by two reasons: (1) the

three dimensions of the model are easy to understand and integrate

within the organization goals due to its simple formulation; (2) is the

approach employed by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) to write the

guides that serve as a basis to produce sustainability reports, being

the GRI guides the most known and employed at global level.

The TBL has been applied to both the public and private sector, i.e., for profit and not for profit organizations [

53]. However, as pointed by Elkington [

54],

the TBL is not exempt from critics. Recently, he stated that “the

Triple Bottom Line has clearly failed to bury the single bottom line

paradigm” [

55]. Gary and Milne [

56],

point to the fact that in case of exchange among the three different

types of final outcomes, it is the financial outcome the one that

becomes more important over social and environmental outcomes. Thus, in

practice, social and environmental outcomes are subordinate to

businesses’ profitability. Likewise, McDonough and Braungart [

57]

criticize TBL for being a measure of “bottom line”. Therefore, TBL

would be providing strategies to firms addressed to minimizing negative

outcomes instead of levering the design of sustainable products and

processes as a starting point for businesses, thus, preventing negative

outcomes.

The TBL and the ECG model share the

triple dimension as a basis to build up their sustainability. For us,

the ECG model goes beyond the TBL in the sense that it takes into

consideration not only the outcomes for the different stakeholders but

also the path followed to get those outcomes. That is, it is not only

what you got it is also how you got it what matters.

2.4. Corporate Sustainability, Integrated Reporting, and ECG Model

The concept of CS has its origins in the relationship between CSR and sustainability [

58]. The Brundtland Commission [

1] employed the concept for the first time in its report of 1987.

Despite the different points of view arisen around sustainability [

59], all of them share the following traits: economic viability, full respect for the environment and be socially equitable [

2,

60].

Since

1987, the United Nations has held a number of summits and conferences

from which several agreements on sustainability goals have been made.

The last one has been the Summit of 2015 which set the seventeen

sustainable development goals to be achieved in 2030: (1) no poverty,

(2) zero hunger, (3) good health and well-being, (4) quality education,

(5) gender equality, (6) clean water and sanitation, (7) affordable and

clean energy, (8) decent work and economic growth, (9) industry,

innovation and infrastructure, (10) reduced inequalities, (11)

sustainable cities and communities, (12) responsible production and

consumption, (13) climate action, (14) life below water, (15) life on

land, (16) peace, justice and strong institutions and (17) partnerships

for the goals.

From its part, the Dow Jones

Sustainability Index (DJSI) defines CS as a business approach that

pursues the long run creation of value for shareholders by means of

taking advantage of opportunities and, at the same time, performing

effective management of the inherent risks to economic, environmental

and social development. Such definition goes beyond the mere concept of

environmental sustainability, providing a strategic focus based on value

creation [

61] which differentiates it from CSR [

62].

Despite it, DJSI does not take into consideration the creation of value

for the rest of the stakeholders (only shareholders). This trait

differentiates it from the ECG model.

Furthermore,

the CS approach, as SHV approach, does not consider business’ ethical

behavior or let this issue in a second term, which impedes the firm to

take full responsibility for its actions and give a response to the

legitimate stakeholders’ expectations [

42].

Unlike the CS approach, the ECG model puts ethical behavior in the core

of business management, placing it on the first level, which turns such

an approach into somewhat global and integrative.

In the same way that economic performance can and must be measured, the same consideration is applicable to sustainability [

63,

64].

This goal can be achieved through a system of non-financial indicators

to measure organizational performance and impact in terms of social and

environmental concerns [

65,

66].

Until

recently, firms did not have any legal duty of providing non-financial

information. In this sense, in 2014 the European Directive 2014/95/UE

included the duty of performing a non-financial statement (NFS) for

large firms. Those with an overall Balance Sheet above 20 millions of €

or a net revenue above 40 millions of €, of public interest, with their

headquarters located at any country of the EU or listed on any of the EU

stock market and with more than 500 employees by the end of the fiscal

year. Such an NFS must include information related to (1) business model

description (activities performed and essential information about how

these activities are performed); (2) an explanation on policies and

procedures (including environmental and social concerns, staff, human

rights and corruption prevention); (3) the main risks related to the

issues included in point 2 and how they can be associated with the

firm’s core businesses; (4) key non-financial indicators (KPI), relevant

to the firm’s core business. In case these indicators were not

provided, indicate the reason/s why they were not applied.

In the present, the most extended non-financial reporting come from ‘Global Reporting Initiative’ (GRI), since 1999 [

67].

GRI is a not-for-profit independent international organization based on

network structure. In its activities participate thousands of

professionals and organizations from a number of industries, communities

and world regions (

www.globalreporting.org).

Up to July 2018, the version in force is G4 designed in 2013 and

launched in 2014. From July 2018, a new version based on four

interrelated modules (Universal, Economic, Environmental and Social) has

substituted G4.

An important milestone in

terms of corporate sustainability reporting happened in 2010 when the

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) developed a global

integrated report (IR) for the first time. The purpose was to build up a

set of corporate reporting rules internationally accepted and to

overcome the existing problems of over-information, lack of clarity and

reliability [

68,

69].

According to IIRC (

www.integratedreporting.org),

“an IR is a concise communication about how an organization’s strategy,

governance, performance, and prospects, in the context of its external

environment, lead to the creation of value in the short, medium and

long-term”. In other words, IR contains the essentials about financial,

social, environmental and corporate governance information by

summarizing it in one report. Thus, such report becomes the firm’s main

picture facing third parties [

70]. Hence, IR goes beyond sustainability reporting being the natural next step [

71,

72].

In the present, we can observe an exponential growth in the number of

reports included in the GRI database as “integrated” reports. They must

include: (1) an overall vision on the organization and its environment

(the organization’s scope, the legal, political, social and

environmental issues that can affect the organization and its value

creation); (2) governance (how the organization’s governance structure

is and how it can lever the organization’s value creation in the short,

medium and long-term); (3) business model (the organization’s recipe to

create value); (4) risks and opportunities (specify the main risks and

opportunities affecting the organization and how they can support the

organization’s ability to create value); (5) strategy and resource

allocation (what is the organization’s last purpose and how it will do

it); (6) performance and strategic goals within the time frame; (7)

perspectives (specify the organization’s main challenges and

uncertainties to implement its strategy); (8) essential assumptions

(determination of the relevant aspects to be reported and how they are

quantified and evaluated).

It is important to

note that GRI guides recommend, despite it is not mandatory, the

verification of the IR (which includes non-financial information). Such

verification should be in charge of an independent expert who has to

produce his/her own conclusions on the reliability and adequacy of the

information (compared with standard values). To perform this

verification process, IIRC has developed a set of international rules

and standards. Therefore, ensuring comparability and credibility to the

stakeholders to whom the information is addressed. These standards are

commonly known as “International Standards on Assurance Engagement”

(ISAE). Among them, we point out: AA1000 APS and ISAE 3000. Sometimes

both are combined as they show complementary traits.

Moreover,

there are independent agencies capable of assessing any type of

organization worldwide in terms of CS and IR. These agencies pick up the

relevant information from different sources (public reports, the

corporate website and others), later on, they contrast it by sending

questionnaires to third parties (NGOs, consumers associations,

environmental associations, unions). Once the information has been

obtained and contrasted, the results are expressed in terms of

measurable variables for every one of the analyzed dimensions. These

results allow classifying the organizations involved in the assessment

and their countries of origin. During the last years a number of

sustainability agencies have proliferated at a global level (i.e.,

EIRIS, Sustainalytics, Oekom Research AG, MSCI ESG Research and

RobecoSam Sustainability Investing). All these agencies work with the

methodology known as Socially Responsible Investment (SRI), a process

that takes into consideration social, environmental and corporate

governance criteria to support the investment making decision process.

Such a process consists of two phases: the first one is normalization

(setting up and disseminating the principles of SRI) and the second one

is screening or social rating (checking and certifying the firm

accomplishment of SRI principles). By its part, MSCI ESG rates more than

3000 corporations in the USA according to three criteria: environmental

(climate change and clean technologies, pollution, toxic wastes and

recycling), social (investment in the community, diversity and equal

opportunities at workplace, human rights and labor relations) and

corporate governance. This rating also includes another component

related to products and processes related to the exclusion of investment

in products like the alcoholic ones, tobacco, betting houses, arms

industry and nuclear industry. In this process, the above-mentioned

criteria are classified as strengths or weaknesses and scored with 1 or 0

points [

73]. In Europe, Vigeo-Eiris is the leader rating agency. It employs the Equitics

®

model, based on internationally recognized standards to assess to what

point the firms take into consideration their goals in terms of CSR in

their strategy definition and implementation. This model distributes

scores in six dimensions: human rights, environment, corporate behavior,

corporate governance and community participation [

73].

From its part, the ECG model [

13]

takes many of the indicators employed by IR, adds other indicators and

offers a global and integrative insight on businesses, but it tries to

promote changes not only inside the businesses but also at the social

level. In this sense, businesses are considered as a change lever, a

force for good. However, the ECG model only considers social and

environmental concerns and tries to improve the measurement of

stakeholders’ management in terms of social and environmental concerns.

This is because the ECG assumes that economic and financial reporting

are currently well developed and grounded; thus, the gap exists in the

fields of social and environmental outcomes measurement.

The

ECG model employs the Common Good (CG) matrix as the tool to manage and

measure the contribution of the business to the common good [

13,

16,

17].

In short, the CGM is the framework that the ECG model proposes to make

compatible the creation of economic, social and environmental value and

to measure the ability of the businesses to integrate the different

types of value in their business model. This way, we argue that the CGM

can be considered as a tool to lever business models based on corporate

sustainability.

Such a matrix relates the

firm’s behavior in terms of the general principles and values of human

rights, grouped into four categories (“human dignity”, “solidarity and

social justice”, “environmental sustainability” and “transparency and

co-determination”), to the stakeholders grouped into five categories

(“suppliers”, “owners, equity and financial services providers”,

“employees”, “customers and business partners” and “social

environment”). Hence, the CGM employs as one of its bases the

Stakeholders approach [

14] to measure the business contribution to the common good.

Hereafter, we proceed to analyze such aspects for every one of the stakeholders considered in the CGM [

74].

According

to the ECG model, the relationship between the business and its

suppliers should be based on the promotion of human dignity in the

supply chain. In this sense, businesses have to be conscious of their

responsibility for the value network in which they participate. Thus,

the criteria to select suppliers are proper work conditions (wages and

labor rights), environmental aspects (raw materials and sources of power

employed), social effects on other groups and regional alternatives.

The model proposes the prioritization of regional, green, social

suppliers to avoid carbon print, the control of risks (i.e., pollution)

related to products/services and the payment of fair prices in origin.

From an entrepreneurial point of view, we conclude that the ECG model

helps to lever local entrepreneurship due to the proximity criterion to

select suppliers; this way, it contributes to the local economic

development. Furthermore, given the prioritization of social criteria,

it also creates opportunities for local social enterprises.

The

ECG Business behavior in regards to its funding is based on ethical

financial management. To do so, businesses prioritize operation with

ethical banking and invest their surplus in ethical and environmentally

sustainable projects. The matrix also advocates for strengthening

self-funding and fostering the funding coming from commercial exchanges

between businesses. Hence, we can conclude that The ECG model drives to

the implementation of a private financial system based on ethical and

social values.

On the other hand, the

relationship between The ECG businesses and their employees is also

based on ethical human resources management (HRM). HRM is one of the

most valuated set of practices by the firms, as it drives to appropriate

management of human capital, can create a good working environment and

connects people and firms. This way, HRM must drive to ensure human

dignity at the workplace through the creation of healthier working

conditions based on freedom in the workplace and cooperation. The

proposed criteria are workplace quality, equality, fair distribution of

work loading, social, ethical and environmentally friendly behavior

promotion among employees, fair distribution of the income generated and

keeping internal democracy and transparency in the decision making

process.

In relation to the business

relationship with its customers and competitors, The ECG model advocates

for fair sales management. The goal is to treat customers as business

partners by putting into practice long-term relationships based on

conscious consumerism and ethical buying practices. The CGM proposes as

criteria: the use of social marketing practices, employee’s training in

relation to fair commercial practices, employees’ compensation systems

in relation to sales targets and customers’ participation in the

business decisions related to the offer of ethical and green

products/services. This way, The ECG model promotes conscious

consumerism and business sustainability not only in the business that

applies the model but also in its customers’ behavior. Heidbrink et al. [

75],

who have done qualitative research on the ECG model, pointed out that

it has the potential to promote a post-growth economy as consumers are

asked if they really need the product or service of a company.

Finally,

the ECG model also proposes an ethically driven environmental

management. In this sense, The ECG businesses define themselves as

citizen organizations socially responsible with a strong commitment to

the social environment in which they operate. To do so, the CGM proposes

the following criteria: human needs satisfaction assessment, return a

part of the profits to the local community, reduction of the effects on

the environment at the minimum possible level, minimize dividends

distribution and set up transparency and participation systems to ensure

social co-determination and transparency.

From

the application of the CGM dimensions and indicators, it is possible to

produce the CGBS which is an integrated report that includes social and

environmental information. Such report also includes improvement

measures and can be verified as in the case of IR.

The

verification process in the ECG model can be performed by means of a

peer to peer procedure (similar to benchmarking) or by an external audit

(approved auditors). There exists a support agency for the common good,

which is in charge of auditors training, auditors approving, advisors

training and advisors approving. Furthermore, this agency has set up a

system to recognize businesses achievements when they perform the whole

process. The term employed to perform the ranking of the firms is

“seed”. Then, they qualify with one seed the businesses that have

produced their CGBS, two seeds if the businesses also followed an audit

peer to peer, and three seeds if the businesses produced their CGBS and

also followed an external audit. Such agencies take the form of

associations that operate at country and/or regional level. Currently,

there are Associations for the promotion of the Economy for the Common

Good in nine different European countries: Austria, Germany,

Switzerland, Italy, Spain, France, Sweden, United Kingdom and The

Netherlands. There exists another association in Chile.

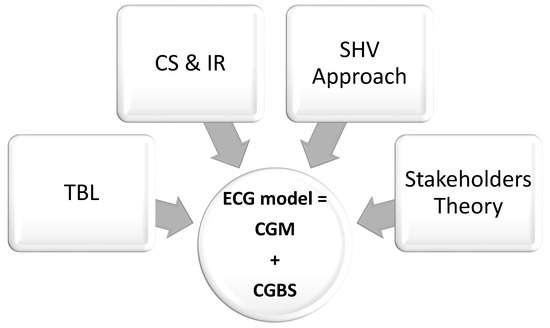

below, summarizes the relationships of the ECG model and its

implementation-control tools (the CGM and the CGBS) with the

pre-existing models (TBL = Triple Bottom Line, CS & IR = Corporate

Sustainability and Integrated Reporting, SHV = Shared Value and,

Stakeholders’ Theory) to capture non-financials based on sustainability

approach.

Figure 1.

The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) model’s origins.