The Common Good Balance Sheet, an Adequate Tool to Capture Non-Financials?

Publicación del primer artículo empírico sobre la Economía del Bien Común en la revista internacional Sustainability

El equipo de investigadores de la

Cátedra de Economía del Bien Común de la Universidad de Valencia

publica, junto con el creador del modelo Christian Felber, el primer artículo empírico sobre la Economía del Bien Común en la revista internacional Sustainability, revista con factor de impacto 2.592 en el JCR y especializada en la sostenibilidad y el desarrollo sostenible.

En relación con la medición del rendimiento organizativo, hay una creciente preocupación por la creación de valor para las personas, la sociedad y el medio ambiente.

La información corporativa tradicional no cumple adecuadamente las

necesidades de información de las partes interesadas para evaluar el

rendimiento potencial de una empresa y el futuro. En este sentido, los

profesionales y los especialistas han desarrollado nuevos marcos de información no financieros

desde una perspectiva social y medioambiental, dando a luz el campo del

Integrated Reporting. El modelo del Economía del Bien Común y sus

herramientas para facilitar la gestión y la gestión de la sostenibilidad

pueden proporcionar un marco para hacerlo.

El estudio describe los fundamentos

teóricos de la investigación de campo de la administración empresarial

en que se basa el modelo de la EBC. Además, este trabajo es el

primero que valida empíricamente estas escalas de medida, tratándose,

por tanto, de la primera investigación cuantificada sobre el modelo de

la EBC en una muestra de 206 empresas europeas.

https://www.uv.es/catedra-economia-bien-comun/es/publicaciones/primer-article-empiric-ebc.html

The Common Good Balance Sheet, an Adequate Tool to Capture Non-Financials?

1

IASS Berlin-Potsdam, Berliner Straβe 30, DE 14467 Potsdam, Germany

2

Business Administration Department, Faculty of Economics, University of València, Tarongers Av., 46022 València, Spain

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Sustainability 2019, 11(14), 3791; https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143791

Received: 13 June 2019 / Revised: 3 July 2019 / Accepted: 8 July 2019 / Published: 11 July 2019

(This article belongs to the Section Economic, Business and Management Aspects of Sustainability)

In relation to organizational performance measurement, there is a

growing concern about the creation of value for people, society and the

environment. The traditional corporate reporting does not adequately

satisfy the information needs of stakeholders for assessing an

organization’s past and future potential performance. Practitioners and

scholars have developed new non-financial reporting frameworks from a

social and environmental perspective, giving birth to the field of

Integrated Reporting (IR). The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) model

and its tools to facilitate sustainability management and reporting can

provide a framework to do it. The present study depicts the theoretical

foundations from the business administration field research on which the

ECG model relies. Moreover, this paper is the first one that

empirically validates such measurement scales by applying of Exploratory

Factor Analysis on a sample of 206 European firms. Results show that

two out of five dimensions are appropriately defined, along with some

guidelines to refine the model. Consequently, it allows knowledge to

advance as it assesses the measurement scales’ statistical validity and

reliability. However, as this is the first quantitative-driven research

on the ECG model, the authors’ future research will confirm the present

results by means of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA).

View Full-Text

En relación con la medición del rendimiento de las organizaciones, existe una creciente preocupación por la creación de valor para las personas, la sociedad y el medio ambiente. La presentación tradicional de informes empresariales no satisface adecuadamente las necesidades de información de las partes interesadas para evaluar el posible rendimiento pasado y futuro de una organización. Los profesionales y académicos han elaborado nuevos marcos de presentación de informes no financieros desde una perspectiva social y ambiental, dando origen al campo de la presentación de informes integrados (IR). El modelo de Economía para el Bien Común (ECG) y sus instrumentos para facilitar la gestión de la sostenibilidad y la presentación de informes pueden proporcionar un marco para hacerlo. En el presente estudio se describen los fundamentos teóricos de la investigación de campo de la administración de empresas en que se basa el modelo ECG. Además, este documento es el primero que valida empíricamente esas escalas de medición aplicando el análisis factorial exploratorio a una muestra de 206 empresas europeas. Los resultados muestran que dos de las cinco dimensiones están adecuadamente definidas, junto con algunas directrices para perfeccionar el modelo. En consecuencia, permite avanzar en el conocimiento al evaluar la validez estadística y la fiabilidad de las escalas de medición. Sin embargo, como se trata de la primera investigación de carácter cuantitativo sobre el modelo de ECG, la futura investigación de los autores confirmará los resultados actuales mediante el análisis factorial de confirmación (CFA).

En relación con la medición del rendimiento de las organizaciones, existe una creciente preocupación por la creación de valor para las personas, la sociedad y el medio ambiente. La presentación tradicional de informes empresariales no satisface adecuadamente las necesidades de información de las partes interesadas para evaluar el posible rendimiento pasado y futuro de una organización. Los profesionales y académicos han elaborado nuevos marcos de presentación de informes no financieros desde una perspectiva social y ambiental, dando origen al campo de la presentación de informes integrados (IR). El modelo de Economía para el Bien Común (ECG) y sus instrumentos para facilitar la gestión de la sostenibilidad y la presentación de informes pueden proporcionar un marco para hacerlo. En el presente estudio se describen los fundamentos teóricos de la investigación de campo de la administración de empresas en que se basa el modelo ECG. Además, este documento es el primero que valida empíricamente esas escalas de medición aplicando el análisis factorial exploratorio a una muestra de 206 empresas europeas. Los resultados muestran que dos de las cinco dimensiones están adecuadamente definidas, junto con algunas directrices para perfeccionar el modelo. En consecuencia, permite avanzar en el conocimiento al evaluar la validez estadística y la fiabilidad de las escalas de medición. Sin embargo, como se trata de la primera investigación de carácter cuantitativo sobre el modelo de ECG, la futura investigación de los autores confirmará los resultados actuales mediante el análisis factorial de confirmación (CFA).

Introduction

The

Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development as the one that

meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of

future generations to meet their own needs [1].

With

corporate sustainability (CS) as the business approach that deals with

sustainable development, in the last 20 years, a number of scholars have

provided different definitions of the subject. All of these definitions

of CS point to the need to integrate economic, social and environmental

aspects in ordinary firms’ management [2,3,4].

Therefore, business practice should operationalize social and

environmental sustainability. To do so, organizations have to implement

management instruments, concepts and systems, i.e., sustainability

management tools [5].

On

the other hand, in terms of an organizational performance measurement,

one can realize how there is a growing concern on the creation of value

for people, society and the environment. Thus, challenging the

traditional financial business reporting model. According to Flower [6],

traditional corporate reporting does not adequately satisfy the

information needs of stakeholders for assessing an organization’s past

and future potential performance. As a consequence, practitioners and

scholars have developed new non-financial reporting frameworks from a

social and environmental perspective. This way, giving birth to the

field of Integrated Reporting (IR), Dumay et al. [7] provide a structured literature review of the field of IR from its starting point up to date.

In

accordance with the above mentioned, for authors, it could be useful

for the organizations to integrate sustainability management and

reporting in one tool to facilitate the implementation and control of

sustainability management. The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) model

and its tools facilitate sustainability management and reporting; The

Common Good matrix (CGM) and the Common Good Balance Sheet (CGBS) can

provide a framework [8,9].

Following the triple bottom line approach [10], Felber [11,12]

proposes an alternative model: the ECG model, of which the purpose is

to achieve full respect for human rights-related fundamental values

within companies worldwide and, thus, a more employee-centered viewpoint

of firms based on cooperation and the prosecution of general interest;

hence, shedding light on the need to balance economic, social and

environmental outcomes. The ECG model has as main goals the business

contribution to the common good and cooperation instead of profit spirit

and competition. From this point of view, economic growth and money are

not goals by themselves; instead, they are considered means to achieve

human welfare and quality of life for people [13].

The ECG model values are, essentially, the universal and basic

principles of human rights: human dignity, solidarity and social

justice, ecological sustainability and democratic participation and

transparency.

The ECG model employs the CGM as the tool to guide and measure the contribution of the business to the common good [13].

In short, the CGM is the framework that the ECG model proposes to make

compatible the creation of economic, social and environmental value and

to measure the ability of the businesses to integrate the different

types of value in their business model. This way, we argue that the CGM

can be considered as a tool to lever business models based on corporate

sustainability.

Furthermore, the CGM is the

base to assess businesses in terms of their contribution to the common

good, as it serves as the base to work out the CGBS. The CGBS is the

tool that the ECG model proposes to measure business success in terms of

economic, social and environmental impacts by means of scores, taking

as a reference the stakeholders’ approach [14].

In

the present work, the authors will perform a statistical validation of

the metrics employed in the CGBS and the CGM to measure the

organizations’ contribution to the common good in terms of their ability

to create different types of value: 1. Human dignity; 2. Solidarity and

social justice; 3. Environmental sustainability; and 4. Transparency

and Co-determination.

To do so, the authors

employed a quantitative approach. Thus, authors tested the CGBS and the

CGM measurement instruments by means of exploratory factor analysis

(EFA) based on principal component analysis (PCA).

From

an overall population of 400 European firms that implemented the ECG

model by applying the CGM and producing the CGBS (being all these CGBS

audited), the authors got a sample of 206 European firms from Germany,

Austria, Switzerland, Italy and Spain. The data-gathering took place

through an online survey during the first quarter of 2018.

This

way, the authors validated the measurement instruments employed in the

CGBS and the CGM. Therefore, they concluded that the CGBS resulted in an

adequate tool to capture non-financial value creation.

The

ECG model provides an alternative framework to implement CS management

and reporting in an integrated way. Hence, it can contribute to

overcoming critics on IR limitations [14].

The

current study is the first one that has empirically validated by means

of quantitative methods (EFA) the metrics employed in the CGBS and the

CGM; consequently, it allows knowledge to advance as it checks their

statistical validity and reliability. This way, this paper contributes

by shedding light on the different theoretical foundations tied to the

business administration field research that have served to ground the

ECG model and, at the same time, by means of the statistical validation

of the measurement scales of the model it provides an assessment that

can serve as a basis to refine a model that is currently in operation in

a number of firms worldwide (mainly in Europe). Consequently, the

results we got are relevant to scholars and practitioners.

Hence,

the objectives of the present paper are: (1) review the different

approaches that constitute the theoretical ground of the ECG model and

its implementation-control tools, (2) assess whether the measurement

scales proposed in the CGBS are adequate metrics to capture

non-financials by integrating measures of social and environmental value

creation for the key stakeholders, that is following a holistic value

concept, and (3) provide guidelines to refine the measurement scales.

2. Theoretical Framework

The ECG model [13]

provides an organizational behavior model that can be translated into a

set of interrelated management-control tools. Such model can be adopted

by whatever type of organization: from the public or private sector,

for profit or not for profit organizations. Thus, in the eyes of the ECG

model, maximizing profit is not the last purpose of a firm; instead,

profit becomes a means through which firms can create different types of

value to contribute to the common good.

The

fact of considering profit as a means to achieve the common good may

involve the classification of the ECG as both a social and

entrepreneurial innovation process. This way, the ECG allows to solve

social needs and, at the same time, to create new social relations and

reinforce economic value creation [15].

On

the other hand, scholarship has deeply analyzed the factors that drive

businesses to succeed or fail. To do so, academia has produced several

theoretical and empirical works that set up a number of theories and

approaches in the field of business administration. However, up to date,

there are no studies focused on the firms that operate under the ECG

model. Despite this, some approaches and theories developed in the

business administration field to explain how firms can achieve superior

economic and financial performance to their rivals can be redefined to

analyze the ECG firms’ behavior [9,16,17].

One

of the first changes that one can appreciate when analyzing the ECG

model is the one in the goals hierarchy, a consequence of the prevalence

of common good over profitability. According to Aristotle, this order

of things is the expression of a true “oikonomia”, whereas the

prevalence of profit over the common good as its opposite:

“chrematistiké” [18].

Defining the common good as the (old and) new bottom line of economic

activities requires a new approach to measure a business way to success.

The CGM and the CGBS are the tools that allow to manage, measure and

monitor the firm’s behavior in terms of social and environmental

concerns in an integrative way. Thus, they involve feedforward,

concurrent and feedback control. Consequently, the CGM and the CGBS

complement the information provided by the financial Balance-sheet and

the income statement of a firm and help to implement sustainable

business models. This way they make possible to manage and monitor the

firm’s behavior in terms of sustainability based on the intersection of

the three dimensions: economic, social and environmental. Therefore, we

can conclude that by putting the ECG model into practice allows the

co-creation of economic, social and environmental value and, thus, it is

aligned with the CSR approach. In the following sub-sections, we show

the different approaches from which the ECG model derives and point the

main contributions that ECG provides over those approaches. The reader

must keep in mind that the ECG model tries to integrate and improve

previous approaches by advancing on pre-existing knowledge.

2.1. Stakeholders Theory and ECG Model

The Stakeholders theory [14,19,20,21,22]

holds that those who can influence or be influenced by the actions of

an enterprise (groups or individuals) must be considered as an essential

part of business strategy. Such theory has been taken as a base to

develop other topics as for example CSR [23,24]

or in the framework of corporate politics, that is, the attempts to

influence political institutions and/or political actors in favor of the

business interests [25]. Hence, this theory places stakeholders in the core of business attention but does not refer to how to manage them [26,27].

The

extant literature advocates for IR to take into consideration

stakeholders’ opinion and allow their participation in the process. The

implication of stakeholders in the process of producing an IR is key to

ensure the implementation of sustainability management, because this way

the organizations can identify the key social and environmental

concerns on which they can work to enhance their positive impacts and

minimize the negative ones [28,29].

Thus, Bellantuono et al. [28]

point to the current non-existence of specifications on how to get the

active participation of stakeholders. According to them, the research

body on quantitative-based techniques to lever stakeholders’

participation and management is still scarce. In this sense, the ECG

model can provide a framework to facilitate sustainable-driven

stakeholders’ management. To do so, it takes qualitative variables

related to business sustainability and stakeholders as a reference and

turns them into scores.

In the ECG model,

organizations employ the CGM to work out the CGBS. Through this matrix

the ECG model measures the degree of relation between the business

activities that the organization holds with its different stakeholders

(suppliers, owners, equity and financial service providers, employees,

customers and business partners and social environment) in terms of the

human and ethical values measured in the model (human dignity,

solidarity, and social justice, environmental sustainability and

transparency and co-determination). Therefore, we can affirm that the

CGM and the CGBS are tools that allow to manage and measure the business

relationships with its stakeholders taking as a basis the human and

ethical values. Furthermore, the ECG model also incorporates a

multi-stakeholders approach [30]

which considers that the business creation of value should be spread

among the different stakeholders (internal and external to the

organization).

However, we hold that the ECG

model goes beyond the stakeholders’ management as the business last

purpose is its contribution to the common good [31].

Being this contribution measured as its contribution to human dignity,

solidarity, social justice, environmental sustainability and

transparency and co-determination in relation to the business

stakeholders. By specifically considering the business stakeholders

(grouping them into five categories), the CGM allows to identify

weaknesses in regards of every one of the stakeholders’ management and,

thus, pointing out the areas that can be improved.

2.2. Shared Value Approach and ECG Model

Porter and Kramer [32]

(p. 6), defined shared value (SHV) as “… policies and operating

practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while

simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the

communities in which it operates. Shared value creation focuses on

identifying and expanding the connections between societal and economic

progress …”

Hence, the underlying idea is that

firms can simultaneously create economic, social and environmental value

(i.e., customer’s welfare, natural resources over-exploitation, key

suppliers’ sustainability and/or disadvantage situation of local

communities in which the company operates) [33]. By all what has been pointed before, Porter and Kramer [34]

pointed to SHV to be a concept that goes beyond Corporate Social

Responsibility (CSR). According to them, CSR conceives social value

creation as somewhat peripheral and, always subordinate to economic

value creation, in the firm’s strategy. In this sense, for them, CSR

policies are the consequence of the firm’s search for social legitimacy,

thus, maximizing short-term profits [32].

Therefore,

by means of SHV, they redefine capitalism borders as the focus on a

different aspect to lever the businesses’ competitive capacity [35]:

i.e., reconceiving products and markets, redefining productivity in the

value chain and developing local clusters. According to them,

reconceiving products and markets consists of identifying the new needs

of societies in fields of healthcare, housing, environment, etc.,

generating innovating products to fulfill those needs co-creating value

for the environment, society and businesses. On the other hand, by means

of redefining productivity in the value chain, i.e., reconfiguring the

activities of the value chain from the perspective of the SHV,

businesses enhance the use of resources, logistics, energy and

employees’ productivity, thus minimizing resource waste. In addition,

local clusters development allows the implementations of improvements in

different business areas by means of cooperation with local businesses

(suppliers, customers, competitors) and also with different types of

local institutions (business associations, local bodies, etc.).

However,

a strategy based on SHV is a bet for the long term as their outcomes

can involve longer time period and higher initial investment “… higher

return and broader strategic benefits to all the participants …” [32] (p. 4).

As

in the case of the ECG model, such approach confers an important role

to market transparency, as well as to cooperation as an essential

condition to create SHV (i.e., cooperation between the firm and its

supply chain) [36,37]. However, unlike the ECG model, SHV model does not advocate for replacing competition with cooperation.

Another

key difference between both models is the role they give to business’

profits. In the case of SHV, the underlying idea consists of the

simultaneous co-creation of social (in a broad sense which includes

environmental) and economic value. Therefore, SHV considers social and

economic value creation as goals at the same level. In this sense, the

SHV model provides full legitimacy to business growth as a strategic

goal. Conversely, the ECG model considers business’ profits and economic

value creation merely as a means that allows businesses to contribute

to the common good. That is, as a mean to generate social and

environmental value.

Despite these differences, the underlying logic proposed by Porter and Kramer [32] about how to create SHV can lever the future development of the ECG model [38,39].

Some of the actions that drive to SHV creation are also a way to

integrate the ECG values into business behavior: human dignity,

solidarity, social justice, environmental sustainability, transparency

and co-determination.

However, we must take

into consideration that SHV approach does not include business’ ethical

values; instead, such issues are relegated to a second term [40].

For that reason, according to the SHV approach, businesses can

co-create social and economic value, but such approach will not

guarantee business’ legitimacy because it does not guarantee that

businesses assume full responsibility for their actions [41,42].

2.3. Triple Bottom Line and ECG Model

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) has its origins in Carroll’s pyramid [43,44,45].

Thus, Carroll’s pyramid points to the existence of four types of CSR:

economic responsibilities (be profitable), located at the base, on a

second level, there are the legal responsibilities (obey the law as

society’s classification of what is right or wrong), on a third level,

we find ethical responsibilities (be ethical, obligation to do what is

right, just and fair and avoid harm), finally, on the top of the

pyramid, we find philanthropic responsibilities (be a good corporate

citizen, contribute resources to the community, improve quality of

life). The ECG framework tries to operationalize the concerns related to

ethical and philanthropic responsibilities of the firms, i.e., those

voluntary adopted by the firms [46,47].

Following Elkington [10]

(p.3), “the sustainable development is compromised with economic

prosperity, environmental quality, and social justice”. Thus, it takes

into consideration three different lines: society, economy and

environment. Society depends on the economy and this, in turns, depends

on the global eco-system whose health is represented as the third line

of the TBL. Society should be viewed in terms of its relations with

economy and eco-system, giving birth to a set of relationships among the

three lines [48,49].

The

TBL model employs a matrix to measure in a quantitative way the impact

generated by the organization from an economic, social and environmental

point of view [50].

Such three dimensions are neither static nor stable; on the contrary,

they are viewed from a dynamic perspective due to the consideration of

the organizational environment in the model. Thus, every one of the

lines acts as a continental platform which can move independently from

the others. So that it can be placed above, below or beside the others;

this involves the possible existence of frictions among them [51,52].

Notwithstanding

the above mentioned, the matrix relates the three basic dimensions

(economy, society and environment) with the organization’s stakeholders

(shareholders, franchisees and/or subsidiaries, employees, customers,

competitors, local communities, humanity, future generations and the

natural world or eco-system).

The model has

succeeded in the last years as it has served to design and implement CSR

policies. It is possible to explain its growth by two reasons: (1) the

three dimensions of the model are easy to understand and integrate

within the organization goals due to its simple formulation; (2) is the

approach employed by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) to write the

guides that serve as a basis to produce sustainability reports, being

the GRI guides the most known and employed at global level.

The TBL has been applied to both the public and private sector, i.e., for profit and not for profit organizations [53]. However, as pointed by Elkington [54],

the TBL is not exempt from critics. Recently, he stated that “the

Triple Bottom Line has clearly failed to bury the single bottom line

paradigm” [55]. Gary and Milne [56],

point to the fact that in case of exchange among the three different

types of final outcomes, it is the financial outcome the one that

becomes more important over social and environmental outcomes. Thus, in

practice, social and environmental outcomes are subordinate to

businesses’ profitability. Likewise, McDonough and Braungart [57]

criticize TBL for being a measure of “bottom line”. Therefore, TBL

would be providing strategies to firms addressed to minimizing negative

outcomes instead of levering the design of sustainable products and

processes as a starting point for businesses, thus, preventing negative

outcomes.

The TBL and the ECG model share the

triple dimension as a basis to build up their sustainability. For us,

the ECG model goes beyond the TBL in the sense that it takes into

consideration not only the outcomes for the different stakeholders but

also the path followed to get those outcomes. That is, it is not only

what you got it is also how you got it what matters.

2.4. Corporate Sustainability, Integrated Reporting, and ECG Model

The concept of CS has its origins in the relationship between CSR and sustainability [58]. The Brundtland Commission [1] employed the concept for the first time in its report of 1987.

Despite the different points of view arisen around sustainability [59], all of them share the following traits: economic viability, full respect for the environment and be socially equitable [2,60].

Since

1987, the United Nations has held a number of summits and conferences

from which several agreements on sustainability goals have been made.

The last one has been the Summit of 2015 which set the seventeen

sustainable development goals to be achieved in 2030: (1) no poverty,

(2) zero hunger, (3) good health and well-being, (4) quality education,

(5) gender equality, (6) clean water and sanitation, (7) affordable and

clean energy, (8) decent work and economic growth, (9) industry,

innovation and infrastructure, (10) reduced inequalities, (11)

sustainable cities and communities, (12) responsible production and

consumption, (13) climate action, (14) life below water, (15) life on

land, (16) peace, justice and strong institutions and (17) partnerships

for the goals.

From its part, the Dow Jones

Sustainability Index (DJSI) defines CS as a business approach that

pursues the long run creation of value for shareholders by means of

taking advantage of opportunities and, at the same time, performing

effective management of the inherent risks to economic, environmental

and social development. Such definition goes beyond the mere concept of

environmental sustainability, providing a strategic focus based on value

creation [61] which differentiates it from CSR [62].

Despite it, DJSI does not take into consideration the creation of value

for the rest of the stakeholders (only shareholders). This trait

differentiates it from the ECG model.

Furthermore,

the CS approach, as SHV approach, does not consider business’ ethical

behavior or let this issue in a second term, which impedes the firm to

take full responsibility for its actions and give a response to the

legitimate stakeholders’ expectations [42].

Unlike the CS approach, the ECG model puts ethical behavior in the core

of business management, placing it on the first level, which turns such

an approach into somewhat global and integrative.

In the same way that economic performance can and must be measured, the same consideration is applicable to sustainability [63,64].

This goal can be achieved through a system of non-financial indicators

to measure organizational performance and impact in terms of social and

environmental concerns [65,66].

Until

recently, firms did not have any legal duty of providing non-financial

information. In this sense, in 2014 the European Directive 2014/95/UE

included the duty of performing a non-financial statement (NFS) for

large firms. Those with an overall Balance Sheet above 20 millions of €

or a net revenue above 40 millions of €, of public interest, with their

headquarters located at any country of the EU or listed on any of the EU

stock market and with more than 500 employees by the end of the fiscal

year. Such an NFS must include information related to (1) business model

description (activities performed and essential information about how

these activities are performed); (2) an explanation on policies and

procedures (including environmental and social concerns, staff, human

rights and corruption prevention); (3) the main risks related to the

issues included in point 2 and how they can be associated with the

firm’s core businesses; (4) key non-financial indicators (KPI), relevant

to the firm’s core business. In case these indicators were not

provided, indicate the reason/s why they were not applied.

In the present, the most extended non-financial reporting come from ‘Global Reporting Initiative’ (GRI), since 1999 [67].

GRI is a not-for-profit independent international organization based on

network structure. In its activities participate thousands of

professionals and organizations from a number of industries, communities

and world regions (www.globalreporting.org).

Up to July 2018, the version in force is G4 designed in 2013 and

launched in 2014. From July 2018, a new version based on four

interrelated modules (Universal, Economic, Environmental and Social) has

substituted G4.

An important milestone in

terms of corporate sustainability reporting happened in 2010 when the

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) developed a global

integrated report (IR) for the first time. The purpose was to build up a

set of corporate reporting rules internationally accepted and to

overcome the existing problems of over-information, lack of clarity and

reliability [68,69].

According to IIRC (www.integratedreporting.org),

“an IR is a concise communication about how an organization’s strategy,

governance, performance, and prospects, in the context of its external

environment, lead to the creation of value in the short, medium and

long-term”. In other words, IR contains the essentials about financial,

social, environmental and corporate governance information by

summarizing it in one report. Thus, such report becomes the firm’s main

picture facing third parties [70]. Hence, IR goes beyond sustainability reporting being the natural next step [71,72].

In the present, we can observe an exponential growth in the number of

reports included in the GRI database as “integrated” reports. They must

include: (1) an overall vision on the organization and its environment

(the organization’s scope, the legal, political, social and

environmental issues that can affect the organization and its value

creation); (2) governance (how the organization’s governance structure

is and how it can lever the organization’s value creation in the short,

medium and long-term); (3) business model (the organization’s recipe to

create value); (4) risks and opportunities (specify the main risks and

opportunities affecting the organization and how they can support the

organization’s ability to create value); (5) strategy and resource

allocation (what is the organization’s last purpose and how it will do

it); (6) performance and strategic goals within the time frame; (7)

perspectives (specify the organization’s main challenges and

uncertainties to implement its strategy); (8) essential assumptions

(determination of the relevant aspects to be reported and how they are

quantified and evaluated).

It is important to

note that GRI guides recommend, despite it is not mandatory, the

verification of the IR (which includes non-financial information). Such

verification should be in charge of an independent expert who has to

produce his/her own conclusions on the reliability and adequacy of the

information (compared with standard values). To perform this

verification process, IIRC has developed a set of international rules

and standards. Therefore, ensuring comparability and credibility to the

stakeholders to whom the information is addressed. These standards are

commonly known as “International Standards on Assurance Engagement”

(ISAE). Among them, we point out: AA1000 APS and ISAE 3000. Sometimes

both are combined as they show complementary traits.

Moreover,

there are independent agencies capable of assessing any type of

organization worldwide in terms of CS and IR. These agencies pick up the

relevant information from different sources (public reports, the

corporate website and others), later on, they contrast it by sending

questionnaires to third parties (NGOs, consumers associations,

environmental associations, unions). Once the information has been

obtained and contrasted, the results are expressed in terms of

measurable variables for every one of the analyzed dimensions. These

results allow classifying the organizations involved in the assessment

and their countries of origin. During the last years a number of

sustainability agencies have proliferated at a global level (i.e.,

EIRIS, Sustainalytics, Oekom Research AG, MSCI ESG Research and

RobecoSam Sustainability Investing). All these agencies work with the

methodology known as Socially Responsible Investment (SRI), a process

that takes into consideration social, environmental and corporate

governance criteria to support the investment making decision process.

Such a process consists of two phases: the first one is normalization

(setting up and disseminating the principles of SRI) and the second one

is screening or social rating (checking and certifying the firm

accomplishment of SRI principles). By its part, MSCI ESG rates more than

3000 corporations in the USA according to three criteria: environmental

(climate change and clean technologies, pollution, toxic wastes and

recycling), social (investment in the community, diversity and equal

opportunities at workplace, human rights and labor relations) and

corporate governance. This rating also includes another component

related to products and processes related to the exclusion of investment

in products like the alcoholic ones, tobacco, betting houses, arms

industry and nuclear industry. In this process, the above-mentioned

criteria are classified as strengths or weaknesses and scored with 1 or 0

points [73]. In Europe, Vigeo-Eiris is the leader rating agency. It employs the Equitics®

model, based on internationally recognized standards to assess to what

point the firms take into consideration their goals in terms of CSR in

their strategy definition and implementation. This model distributes

scores in six dimensions: human rights, environment, corporate behavior,

corporate governance and community participation [73].

From its part, the ECG model [13]

takes many of the indicators employed by IR, adds other indicators and

offers a global and integrative insight on businesses, but it tries to

promote changes not only inside the businesses but also at the social

level. In this sense, businesses are considered as a change lever, a

force for good. However, the ECG model only considers social and

environmental concerns and tries to improve the measurement of

stakeholders’ management in terms of social and environmental concerns.

This is because the ECG assumes that economic and financial reporting

are currently well developed and grounded; thus, the gap exists in the

fields of social and environmental outcomes measurement.

The

ECG model employs the Common Good (CG) matrix as the tool to manage and

measure the contribution of the business to the common good [13,16,17].

In short, the CGM is the framework that the ECG model proposes to make

compatible the creation of economic, social and environmental value and

to measure the ability of the businesses to integrate the different

types of value in their business model. This way, we argue that the CGM

can be considered as a tool to lever business models based on corporate

sustainability.

Such a matrix relates the

firm’s behavior in terms of the general principles and values of human

rights, grouped into four categories (“human dignity”, “solidarity and

social justice”, “environmental sustainability” and “transparency and

co-determination”), to the stakeholders grouped into five categories

(“suppliers”, “owners, equity and financial services providers”,

“employees”, “customers and business partners” and “social

environment”). Hence, the CGM employs as one of its bases the

Stakeholders approach [14] to measure the business contribution to the common good.

Hereafter, we proceed to analyze such aspects for every one of the stakeholders considered in the CGM [74].

According

to the ECG model, the relationship between the business and its

suppliers should be based on the promotion of human dignity in the

supply chain. In this sense, businesses have to be conscious of their

responsibility for the value network in which they participate. Thus,

the criteria to select suppliers are proper work conditions (wages and

labor rights), environmental aspects (raw materials and sources of power

employed), social effects on other groups and regional alternatives.

The model proposes the prioritization of regional, green, social

suppliers to avoid carbon print, the control of risks (i.e., pollution)

related to products/services and the payment of fair prices in origin.

From an entrepreneurial point of view, we conclude that the ECG model

helps to lever local entrepreneurship due to the proximity criterion to

select suppliers; this way, it contributes to the local economic

development. Furthermore, given the prioritization of social criteria,

it also creates opportunities for local social enterprises.

The

ECG Business behavior in regards to its funding is based on ethical

financial management. To do so, businesses prioritize operation with

ethical banking and invest their surplus in ethical and environmentally

sustainable projects. The matrix also advocates for strengthening

self-funding and fostering the funding coming from commercial exchanges

between businesses. Hence, we can conclude that The ECG model drives to

the implementation of a private financial system based on ethical and

social values.

On the other hand, the

relationship between The ECG businesses and their employees is also

based on ethical human resources management (HRM). HRM is one of the

most valuated set of practices by the firms, as it drives to appropriate

management of human capital, can create a good working environment and

connects people and firms. This way, HRM must drive to ensure human

dignity at the workplace through the creation of healthier working

conditions based on freedom in the workplace and cooperation. The

proposed criteria are workplace quality, equality, fair distribution of

work loading, social, ethical and environmentally friendly behavior

promotion among employees, fair distribution of the income generated and

keeping internal democracy and transparency in the decision making

process.

In relation to the business

relationship with its customers and competitors, The ECG model advocates

for fair sales management. The goal is to treat customers as business

partners by putting into practice long-term relationships based on

conscious consumerism and ethical buying practices. The CGM proposes as

criteria: the use of social marketing practices, employee’s training in

relation to fair commercial practices, employees’ compensation systems

in relation to sales targets and customers’ participation in the

business decisions related to the offer of ethical and green

products/services. This way, The ECG model promotes conscious

consumerism and business sustainability not only in the business that

applies the model but also in its customers’ behavior. Heidbrink et al. [75],

who have done qualitative research on the ECG model, pointed out that

it has the potential to promote a post-growth economy as consumers are

asked if they really need the product or service of a company.

Finally,

the ECG model also proposes an ethically driven environmental

management. In this sense, The ECG businesses define themselves as

citizen organizations socially responsible with a strong commitment to

the social environment in which they operate. To do so, the CGM proposes

the following criteria: human needs satisfaction assessment, return a

part of the profits to the local community, reduction of the effects on

the environment at the minimum possible level, minimize dividends

distribution and set up transparency and participation systems to ensure

social co-determination and transparency.

Previously,

there have been four versions of the CGM that have evolved into the 5.0

version in force since May 2017 after seven years of experience since

the ECG model was launched. The 5.0 CGM can be consulted at www.ecogood.org/en/common-good-balance-sheet/common-good-matrix/.

From

the application of the CGM dimensions and indicators, it is possible to

produce the CGBS which is an integrated report that includes social and

environmental information. Such report also includes improvement

measures and can be verified as in the case of IR.

The

verification process in the ECG model can be performed by means of a

peer to peer procedure (similar to benchmarking) or by an external audit

(approved auditors). There exists a support agency for the common good,

which is in charge of auditors training, auditors approving, advisors

training and advisors approving. Furthermore, this agency has set up a

system to recognize businesses achievements when they perform the whole

process. The term employed to perform the ranking of the firms is

“seed”. Then, they qualify with one seed the businesses that have

produced their CGBS, two seeds if the businesses also followed an audit

peer to peer, and three seeds if the businesses produced their CGBS and

also followed an external audit. Such agencies take the form of

associations that operate at country and/or regional level. Currently,

there are Associations for the promotion of the Economy for the Common

Good in nine different European countries: Austria, Germany,

Switzerland, Italy, Spain, France, Sweden, United Kingdom and The

Netherlands. There exists another association in Chile.

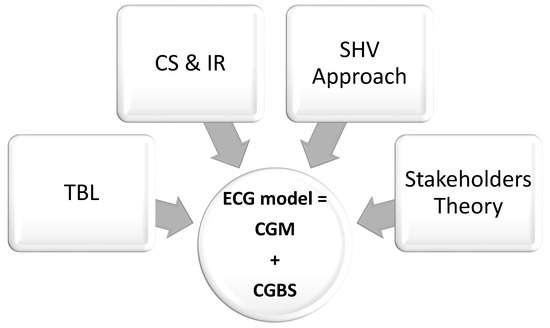

Figure 1

below, summarizes the relationships of the ECG model and its

implementation-control tools (the CGM and the CGBS) with the

pre-existing models (TBL = Triple Bottom Line, CS & IR = Corporate

Sustainability and Integrated Reporting, SHV = Shared Value and,

Stakeholders’ Theory) to capture non-financials based on sustainability

approach.

Figure 1.

The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) model’s origins.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data-Gathering and Sample Profile

To

validate the metrics employed in the CGM and the CGBS, we designed a

questionnaire to be distributed among the firms that have implemented

the ECG model from 2011 to 2017 in Europe. Such questionnaire asked the

firms about the scores they have obtained in the different items

included in the CGM and reported in the CGBS. It also picked up

information on the industry, age, country of origin, number of employees

and turnover, with these variables treated as control variables for

statistical purposes.

We distributed the

questionnaire through an e-mail addressed to the firms’ managers during

the first quarter of 2018. The e-mail contained a link that allowed the

firms to fulfill the questionnaire on the online platform “Survey

Monkey”; they could also upload their CGBS to the platform or send it by

e-mail. This facilitated the data-gathering, as it enabled the

researchers to download the data matrix directly from the online

platform; then, they only had to type the scores of the firms that had

opted for uploading their CGBS or sending them by e-mail.

The

population comprised an overall of 400 European firms that had

implemented the ECG model by producing and auditing a CGBS up to 31

December 2017. We identified the population through the database of the

European Association for the promotion of the Economy for the Common

Good that can be accessed at https://www.ecogood.org/en/community/.

We

sent the questionnaire to the overall population and got an overall of

206 full and valid responses, that is, the sample comprised 51.50% of

the population. Thus, 83.98% of the firms included in the sample

operated in the tertiary sector, 11.17% in the secondary one and 2.43%

in the primary sector. By size, 55.83% were micro-enterprises, 38.35%

SME and 5.83% large enterprises. Five European countries concentrate

most the sample of the ECG firms: Germany (39.8%), Austria (30.1%),

Spain (19.4%), Italy (7.8%) and Switzerland (2.4%). The rest of the

European countries accounted for 0.49% of the sample.

The

firms can obtain a maximum score of 1000 points by applying the metrics

included in the CGM and reported in the CGBS. The average score

obtained by the firms was 497, the median was 498; which means that,

according to the rating employed by the CGBS, most of them fall into the

“experienced” level (between 301 and 600 points). Specifically, 67.96%

of firms in the sample fall into the “experienced” level, 24.27% of the

fall into the “exemplary” level (between 601 and 1000 points). None of

them fall into the “beginner” level (between 1 and 100 points) and 7.77%

of them fall into the “advanced” level (between 101 and 300 points).

3.2. Measures

As

the last purpose of the current study is to statistically test and

validate the measurement scales employed in the CGM and the CGBS, we

took into consideration the dimensions and items included in the 5.0

version of the ECGM and the CGBS (the version currently in force).

Furthermore,

given that the present study includes the European firms that have

implemented the ECG model producing their CGM and CGBS from 2011 to

2017, we had to deal with five different versions of the CGM and the

CGBS. Consequently, the first task to do was to homogenize the measures

and transform them into the 5.0 version. To do so, we employed the

conversion table elaborated by the ECG advisors that have been in charge

of the development of the five versions of the model.

Table 1,

below, depicts the dimensions and measures (items) that the CGM and the

CGBS employ to measure the relationship of the firms with their

stakeholders in terms of social and environmental concerns.

Table 1.

Dimensions and measurement scales of the CGM and CGBS.

3.3. Analysis Technique

To

validate the metrics employed in the CGM and CGBS, we first assessed

whether an underlying structure existed among the measurement

instruments by means of exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Following

Hair et al. [76],

we found EFA to be an appropriate technique because it provides the

tools for analyzing the structure of the interrelationships among a

large number of variables by defining sets of variables (factors) that

are highly correlated. Being factors assumed to represent dimensions

within the data.

Moreover, as the general

purpose of EFA is to find a way to summarize the information contained

in a number of original variables (items) into a smaller set of new,

composite dimensions (factors) with a minimum loss of information, that

is, to search for and define the fundamental constructs or dimensions

assumed to underlie the original variables [77,78];

therefore, EFA is suitable to check whether the structure revealed by

the data set fits the structure proposed in the CGM and the CGBS.

Finally,

we proceed to validate the results of EFA to assess their degree of

generalizability. This issue is critical for the interdependence methods

as EFA. Specifically, in our research, the generalizability of the

results would involve the empirical demonstration that the CGM and the

CGBS are adequate (valid) tools to capture non-financials concerns.

4. Findings

The

starting point to apply any multivariate technique (this includes EFA)

on a data set is to check whether the data set follows a normal

distribution [79]. In our case, as pointed out in Section 3.1,

the average score the firms got by applying the CGBS was 497 whilst the

median of such score was 498. Thus, suggesting a normal distribution of

the data. Furthermore, following Hair et al. [76],

we also checked the statistic value (z) for the skewness and Kurtosis

of the metrics (items) employed in the CGM and the CGBS, along with

Shapiro-Wilks test of normality. Table 2 below depicts the items descriptive statistics.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Normality tests.

As we can observe in Table 2, the Z skewness and Z kurtosis values are closer to or under the conventional value of ± 2.00 [62].

Moreover, the Shapiro-Wilks test confirmed the normality of the data

distribution. Therefore, EFA as a multivariate analysis technique will

produce reliable results.

Thereafter, we

ensured that the correlation matrix fulfills the assumptions to apply

factor analysis. That is, that the data matrix had sufficient

significant correlations to justify the application of factor analysis

(the commonly accepted threshold is 0.30). Table 3

below shows the correlation matrix with the significant correlations at

0.01 level in bold and followed by a * sign. As we can see, most of the

correlations among items were greater than 0.30 and significant at 0.01

level.

Table 3.

Partial correlations and Measures of Sample Adequacy.

In the bottom of Table 3,

we can also find an overall measure of sample adequacy

(Kaiser-Meyer-Olin, KMO) and the Barlett test of Sphericity. With

regards to KMO, it ranges from 0 to 1. According to Kaiser [80,81],

when KMO takes a value greater than 0.8, we are facing a meritorious

level of sampling adequacy. KMO reached 0.846 in our case. Barlett test

of Sphericity is also displayed at the bottom of Table 3;

in our case, we can conclude that the correlation matrix had

significant correlations among, at least, some of the items at 0.01

level. Therefore, we concluded that the data were suitable to apply

factor analysis.

Then, we proceeded to apply

component analysis. We did so because data reduction was our primary

concern as our goal was to determine whether there are any latent

variables among the CGBS items and because this is the first attempt to

validate the metrics of the CGBS, we thought that the most appropriate

choice was to consider the total variance as starting point. However,

although considerable debate remains over which factor model is the most

appropriate, empirical research demonstrated similar results in many

instances. Both factor models arrive at similar results when the

communalities exceed 0.60 for most items [82,83,84,85,86], as in our case.

Table 4

shows the results for the extraction of component factors for the full

set of metrics employed in the CGBS. We decided to employ the VARIMAX

method because it seems to give a clearer separation of the factors [76].

Table 4.

Results for the Extraction of Component Factor: Full set of items.

To determine the number of factors to extract,

we combined the eigenvalues and the percentage of variance criteria.

Thus, only factors having eigenvalues greater than 1 and accounting for

at least 60% of the total variance extracted were retained. As we can

observe in Table 4,

according to the results, we got a five-factor solution which is

consistent with the number of dimensions considered in the CGBS.

Thereafter, we examined the rotated component matrix to achieve simpler and theoretically more meaningful solutions.

Table 5,

below, depicts the VARIMAX-rotated component analysis containing the

full set of 20 items that are the metrics employed in the CGBS. For a

clearer discussion of results, we have moved the tables depicting the

intermediate steps solutions to the Appendix A section and only the final solution is included in the findings section.

Table 5.

VARIMAX-Rotated Component Analysis Factor Matrix: Reduced Sets of 17 items.

As we can observe, in the table (Table A1)

factor loadings below 0.40 have not been displayed as those loadings

were found no significant at 0.05 level given the sample size of 206

observations and a power level of 80% (computations made with GPower

3.1). Table 5

also shows a well-defined structure of factors 1 and 2 with loadings

over 0.70 for the items A1, A2, A3 and A4 in relation to factor 1 and

for the items B1, B2, B3 and B4 in relation to factor 2. The rest of the

structure was not clear.

Moreover, in factor

analysis, items must be unidimensional. That is, they must represent a

single concept. Consequently, each factor should consist of a set of

items loading highly on a single factor, meaning that each dimension

should be reflected by a separate factor [87,88,89,90]. According to the results displayed in the table (Table A1),

the items C3 and E3 were not unidimensional; thus, these items are

candidates to be removed to ensure the items’ unidimensionality. Then,

to assess the consistency to the entire scale, we proceeded to check the

reliability statistics for the full set of 20 items which are depicted

in Table A2.

As we can see in Table A2, the Cronbach’s Alpha of the full model reached 0.801 above the recommended threshold of 0.70 [76].

The Cronbach’s Alpha of the model if the items C3 and D3 were deleted

stayed above such threshold. Therefore, we decided to remove both items

(C3 and D3) and ran the factor analysis again with 18 items.

Table A3

depicts the VARIMAX-rotated component analysis matrix for the reduced

set of 18 items. As we can observe, it also produced a five-factor

solution capturing 77.280% of the Variance extracted by the factors.

Factors 1 and 2 showed a well-defined structure coincident with the

dimensions A (Suppliers Management) and B (Owners, Equity and Financial

Service Providers Management) of the CGM and the CGBS.

However,

in this case, we found D3 to show multi-dimensionality problems, as it

cross-loaded on factors 1 and 5, and D4 not loading on any factor.

Furthermore, some items showed communalities under the recommended

threshold of 0.50. So, we decided to remove D3 and re-estimate the

factor model with a reduced set of 17 items to test for comparability.

Table 5

shows the results of the VARIMAX-rotated component analysis matrix for

the reduced set of 17 items. In this case, factor analysis revealed a

structure of five factors even though the fifth-factor eigenvalue was

slightly below 1. We decided to keep the five factors structure because

the fifth one contributed to increasing the total variance extracted by

5.669. Thus, the five factors captured 78.701% of the variance of the

overall 17 items.

Thereafter, we proceeded to

analyze the factor structure revealed by means of analyzing the results

of the factor analysis. Factor 1 is built upon the items A1, A2, A3 and

A4, all of them with loadings over 0.90. Thus, revealing a well-defined

structure in coincidence with the dimension A (Suppliers Management) of

the CGM and the CGBS. So we labeled factor 1 as Suppliers Management

(SPM). From its part, factor 2 is built upon the items B1, B2, B3 and

B4, all of them with loadings over 0.90. Thus, revealing a well-defined

structure in coincidence with the dimension B (Owners, Equity and

Financial providers Management) of the CGM and the CGBS. Thus, we

labeled factor 2 as Owners, Equity and Financial providers Management

(OEFPM). On their part, factors 3, 4 and 5 show overlaps between the

dimensions C (Employees), D (Customers and Business Partners) and E

(Social Environment). Another important issue revealed by factor

analysis with regards to stakeholders’ management in terms of

environmental sustainability is that items C3, D3, and E3 had to be

deleted to ensure the unidimensionality of the items. This finding

involves that only SPM and OEFPM dimensions include measures of

environmental sustainability in the final model.

In

terms of communalities, in the final solution, all the items showed

communalities above the threshold of 0.50, demonstrating their

appropriateness.

To assess the degree of

consistency of the entire scale (CGBS) we check the Chronbach’s Alpha of

the 17 items model, which reached 0.767, thus confirming the overall

model reliability.

Finally, we checked if the

17 items were statistically different from one another by means of ANOVA

test. It tests for differences in means between the groups, as the

significance level was lower than 0.05 we concluded that the means of

the 17 items were significantly different. To complete the comparison of

the mean, we performed a pairwise comparison of the means of the 17

items by means of a posthoc test. Table A4

shows the F statistics and the significance level corresponding to the

comparison of the means of every pair of items. As we can see, the means

of the 17 items are significantly different one from another and,

consequently, they were measuring different concepts and we did not face

any redundancy among items.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The

present paper aimed to depict the business administration approaches on

which the ECG model relies. Through the previous sections, we proceeded

to perform an analysis by comparison between every one of the

approaches considered and the ECG model; this allowed us to frame it

into the business administration field research and to point out the

contribution that the ECG model has made.

Namely,

we first related the ECG model to the stakeholders’ theory with which

the model shares the need to put stakeholders at the core of the

business management. However, the ECG model goes beyond stakeholders’

theory as, by means of the CGM, it provides guidance to align the

stakeholders’ management with the full respect of human rights.

Thereafter,

we also compared the ECG model to the shared value approach. Although

the SHV approach advocated for the co-creation of economic, social and

environmental value, the ECG considers social and environmental value

creation (i.e., the contribution to the common good) as the last

business purpose, thus giving priority to social and environmental

concerns over profitability.

With the triple

bottom line (TBL) approach, the ECG model shares the idea of measuring

the three different types of value that businesses can create and the

use of a matrix as a tool to manage and measure them. However, in

contrast, the ECG puts social and environmental value over economic

value, while the TBL works with three platforms that are

interchangeable.

Finally, the ECG model is also

related to corporate sustainability (CS) approach and integrating

reporting (IR). The ECG model, when compared to the CS approach, also

advocates for the balance among society, environment and economy, but

unlike CS, it puts ethical behavior in the core of business management.

In contrast, the ECG model employs a multi-stakeholders approach instead

of shareholder approach. These traits make the ECG become a more

complete model to manage sustainability at the business level.

Moreover,

following the CS approach, IR has been developed and spread among

numerous firms around the globe to measure organizational performance in

terms of social and environmental impacts. In this sense, the ECG model

by means of the CGBS provides the framework to measure social and

environmental impacts using scores. In both cases, IR and CGBS can be

verified. However, inasmuch as the CGBS also provides an improvement

plan to the businesses, one can conclude that the ECG model contributes

to the continuous improvement of corporate sustainability management. In

short, the ECG model can become the next step in corporate

sustainability since it completes the pre-existing models and this way

it levers the development of sustainable business models.

The

quantitative part of the study aimed to check whether the measures

employed by the CGM and the CGBS were valid and reliable metrics. To do

so, we applied EFA on a sample of 206 (out of 400) European firms that

had produced and audited a CGBS since 2011.

The

results of EFA revealed a five factors solution. Hence, we concluded

that the dataset showed an underlining structure similar to the one

depicted in the CGBS. However, in regards to the dimensions, only two of

the five factors revealed by EFA coincided with the ones included in

the CGBS (SPM coincided with A and OEFPM coincided with B).

On

the other hand, the other three factors were built upon the overlap of

different dimensions according to the design of the CGBS. For that

reason, we would recommend merging some of the dimensions. Specifically,

factor 3 included 4 items related to the management of employees and

social environment in terms of solidarity and social justice and

transparency and co-determination; factor 4 included 2 items measuring

the management of employees and customers and business partners in terms

of human dignity and, finally, factor 5 included 2 items related to the

management of customers and business partners in terms of solidarity

and social justice and transparency and co-determination in addition to

one item related to the management of social environment in terms of

human dignity. This indicated that the boundaries between the different

stakeholder’s dimensions considered in the model are blurred, while the

distinction between solidarity and transparency and co-determination are

not clear. Thus, these dimensions could be considered as suitable to

merge in a broader dimension.

According to the

results of EFA, 3 out of 5 items aimed at the measurement of the

dimensions C, D and E in terms of environmental sustainability had to be

removed from the model. As a consequence, it would be suitable to

develop new measures of the management of some stakeholders (C, D and E)

in terms of environmental sustainability to be included in a new

version of the CGBS. Therefore, the dimensions C, D and E must be

re-defined and re-structured taking into account the results provided by

means of EFA.

By the considerations made by

the authors in regards to the measurement scales corresponding to the

dimensions C, D and E of the model, we have provided some important

guidelines on what dimensions and how should be redefined. This way, the

present research can have some practical implications if our

recommendations are taken into consideration to refine the model.

Finally,

this study is based on EFA as it is the first one that tries to

validate the CGBS as an adequate tool to capture non-financials. Future

research should confirm these results by means of confirmatory factor

analysis (CFA). Another interesting line for future research will be

assessing whether significant differences in the scores exist by firms’

size, age, economic sector or home country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization,

C.F., V.C. and J.R.S.; methodology, V.C.; software, V.C.; validation,

V.C., C.F. and J.R.S.; formal analysis, V.C.; investigation, J.R.S.;

resources, J.R.S.; data curation, V.C.; writing—original draft

preparation, V.C.; writing—review and editing, V.C.; visualization,

J.R.S.; supervision, J.R.S.; project administration, V.C.; funding

acquisition, J.R.S.

Funding

This research was funded by the Humanistic Management Practices gGmbH.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

VARIMAX-Rotated Component Analysis Matrix: Full set of 20 items.

Table A2.

Reliability Statistics. Full set of items (20).

Table A3.

VARIMAX-Rotated Component Analysis Matrix: Reduced Set of 18 items.

Table A4.

Means pairwise comparison, Anova Post-hoc test.

References

- Brundtland, G.; Khalid, M.; Agnelli, S.; Al-Athel, S.; Chidzero, B.; Fadika, L.; Singh, M. Our Common Future; Brundtland report; United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R.L. Corporate sustainability accounting: A nightmare or a dream coming true? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2006, 15, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Two decades of sustainability & management tools for SMEs: How far have we come? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 481–505. [Google Scholar]

- La Torre, M.; Trotta, A.; Chiappini, H.; Rizzello, A. Business models for sustainable finance: The case study of social impact bonds. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, J. The international integrated reporting council: A story of failure. Crit. Perspec. Acc. 2015, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Bernardi, C.; Guthrie, J.; Demartini, P. Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Acc. Forum 2016, 40, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, F.; Kroczak, A.; Facchinetti, G.; Egloff, S. Economy for the Common Good. DAS in Sustainable Business; Business School Lausanne: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://balance.ecogood.org/ecg-reports/bsl-economy-of-the-common-good.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Frémeaux, S.; Michelson, G. The common good of the firm and humanistic management: Conscious capitalism and economy of communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of the 21st-Century Business; Capstone Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Felber, C. Neue Werte für die Wirtschaft—eine Alternative zu Kapitalismus und Kommunismus; Deuticke: Vienna, Àustria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Felber, C. Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie; Piper: Munich, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Felber, C. Change Everything: Creating an Economy for the Common Good; Zed Books: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- European Economic and Social Committee. The Economy for the Common Good: A Sustainable Economic Model Geared Towards Social Cohesion, EUR-Lex. 2016. Available online: lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/ (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Foti, V.T.; Scuderi, A.; Timpanaro, G. The economy of the common good: The expression of a new sustainable economic model. Qual. Acc. Suc. 2017, 18, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Calvo, V.; Gómez-Alvarez, R. The economy for the common good and the social and solidarity economies, are they complementary? CIRIEC J. Pub. Soc. Coop. Econ. 2017, 87, 257–294. [Google Scholar]

- Dierksmeier, C.; Pirson, M. Oikonomia versus chrematistiké, learning from aristotle about the future orientation of business management. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Reed, D.L. Stockholders and stakeholders: A new perspective on corporate governance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1983, 25, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.L.; Miles, S. Stakeholders: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Adeneye, Y.B.; Ahmed, M. Corporate social responsibility and company performance. J. Bus. Stud. Quart. 2015, 7, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Fu, Q. A Win-win outcome between corporate environmental performance and corporate value: From the perspective of stakeholders. Sustainability 2019, 11, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, S.; Crook, R.; Woehr, D.J. Mixing business with politics: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of corporate political activity. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Buchholtz, A. Business and Society: Ethics and Stakeholder Management, 6th ed.; Thompson Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, F.; Eden, C. Strategic management of stakeholders: Theory and practice. Long Range Plan. 2011, 44, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellantuono, N.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Scozzi, B. Capturing the stakeholders’ view in sustainability reporting: A novel approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S. Stakeholder theory classification: A theoretical and empirical evaluation of definitions. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 142, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J. The Shareholders vs. Stakeholders debate. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Argandoña, A. The stakeholder theory and the common good. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Creating shared value. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Barisan, L.; Lucchetta, M.; Bolzonella, C.; Boatto, V. How does carbon footprint create shared values in the wine industry? Empirical evidence from prosecco superiore PDO’s wine district. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wójcik, P. How creating shared value differs from corporate social responsibility. J. Manag. Bus. Admin. 2016, 24, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin, J.; Schmidt, E. Creating shared value in the hybrid venture arena: A business model innovation perspective. J. Soc. Entrepren. 2011, 2, 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beschorner, T. Creating shared value: The one-trick pony approach. Bus. Ethics J. Rev. 2014, 1, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelini, L.; Fiorentino, D. New business models for creating shared value. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzer, M.; Bockstette, V.; Stamp, M. Innovating for shared value. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- De los Reyes, G., Jr.; Scholz, M.; Smith, N.C. Beyond the “Win-Win” creating shared value requires ethical frameworks. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 59, 142–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, L.P.; Werhane, P.H. Proposition: Shared value as an incomplete mental model. Bus. Ethics J. Rev. 2013, 1, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the value of creating shared value. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]